New season, new art! The Chinese New Year began January 28th and with it brought the Year of the Rooster. Up until the start of the 2018 Chinese New Year, Chinatown Park will host the public artwork Make and Take, which merges modern 3D printing technology with antique Chinese art. A collaboration between Chris Templeman and New American Public Art (NAPA) with the use of an object from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) collection culminates in a 3D-printing kiosk that will produce a limited number of rooster figurines that Greenway visitors can take with them.

Templeman, the artist and designer of the project and an engineer by trade, is not unfamiliar with eclectic and interdisciplinary collaboration, which was evident when I had the opportunity to visit his studio while he worked on the project. Templeman’s work space is unlike what I imagine a typical engineering environment to be. He and the NAPA team have studio space in the Artisan’s Asylum, a community fabrication center in Somerville, MA. The space itself is an interdisciplinary funhouse, thanks to facilities for jewelry making, welding, and bike maintenance; a research lab; a sculpture gallery; and of course, equipment for 3D printing. The space becomes an incubator for creative makers to collaborate with and support one another.

3D-printing technology has been around for more than 30 years, but it is only now beginning to become available for general public use. Templeman describes a 3D-printing Renaissance of sorts, as the original patents on 3D technology and engineering are expiring, thus making it more accessible to a wider audience. He is inclined to direct public attention towards the future of 3D printing and urges us to explore our capacity to utilize it as a technology and an art. His hope is that the artwork’s placement in a bustling corner of Chinatown will spread this notion of an impending horizon of possibilities for 3D printing and increase the visibility and versatility of this technology on a public level. “The technology is real. It’s not magic, so let’s demystify it,” Templeman said.

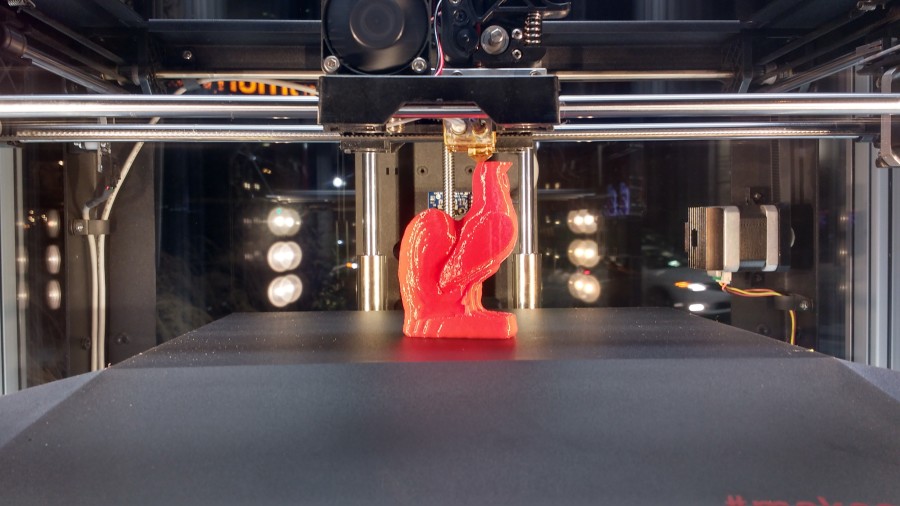

His design reflects his vision. Templeman and NAPA’s eight-foot tall kiosk houses a Fused-Deposition-Modeling 3D printer that sits almost regally on a small, luminescent pedestal. The structure is designed to make the printing process as transparent as possible for the viewer. His team essentially created a clear glass box through which the public can watch the plastic filament thread through the printer as it is melted like hot glue and spliced into a 2D layer which gradually builds upon itself to become the rooster that is deposited into a drop door as if it were a piece of bubblegum in a vending machine. The entire process takes between three and a half to four hours to print one rooster, so if you get lucky, you might be there just in time to collect one over the course of the year – but beware, it’s competitive. Some wait hours to get one of the prized roosters.

In addition to visualizing the printing process, the transparency also pays homage to the history of 3D printing mechanics. Just as we might think of a legacy or interaction between movements and styles of art, there is a similar evolution happening in 3D printing. Templeman cited the RepRap machine – a self-replicating machine that aims to provide open-source, do-it-yourself 3D printers at low costs to hobbyists. Through direct replication as well as influence, the community around the RepRap should be credited and thanked for bringing 3D printing to the masses. The Make and Take printer is a modified Flash Forge Creator Pro. The Creator Pro’s ‘parent’ is the Makerbot Replicator 2. The Replicator 2 is an open source machine ‘child’ of the RepRap.

Templeman is energized by the technical and design challenges he encountered along the way and with his engineering background, it’s the obstacles that spark creativity – and often spur the best solutions. For optimal use, the printer should be kept at 70 degrees Fahrenheit, but a 12-month installation period in the New England climate certainly presents design challenges. To keep the printer within the target temperature range, Templeman installed a heater system inside the kiosk to activate in winter weather, while a fan will cool the space in the hot summer months.

An unforeseen and unfamiliar challenge for Templeman was having so many choices during his design process. He recalls receiving a call from The Greenway’s Public Art Curator Lucas Cowan about the project. Eagerly accepting the commission, he began asking questions about parameters, requirements, and specifications for the artwork. Much of Templeman’s background is in fabricating items that meet specific standards of use determined by the consumer or client. As he worked on the rooster project, he simultaneously calculated designs for a project for the US Navy.

However, for The Greenway he learned to switch mindsets because he had the freedom to make his own artistic decisions. Cowan has said of his curation: “The best thing you can do for an artist is give them money and time – and give them space.” This space was a challenge for Templeman at first, but he began to embrace the possibilities, unfettered from the innumerable criteria that he works with on other projects. “I’m becoming more comfortable with choices,” he said.

Many possibilities arose when Templeman was developing the form for his rooster prototype, which was based on a 3D scan of an artifact from the Museum of Fine Art’s collection. In light of the Chinese New Year, he knew that he wanted to incorporate a traditional or historic rooster figure from Chinese culture in some way, and in his research he came across records of a white porcelain rooster in the MFA collection. The object, measuring around six inches, was recorded as a gift to the MFA from Aimée and Rosamond Lamb in the 19th century and had never been on display in an exhibition. In fact, very little is known about the rooster and this intrigued Templeman.

What is known about the rooster’s history can be gleaned from what we know about the exchange between Chinese artisans and a Western audience in the 19th century. There was a demand for “exotic” art objects produced in the East – a fashion trend that incentivized Chinese artisans to produce small, exportable items for the Western consumer market. Make and Take brings this rooster’s history into a modern context for public consideration. In the 19th century, porcelain was a very modern and in-demand material, quite parallel to the novelty of 3D printing today. Yet with Make and Take, the public is invited to freely take these replicas – thus, a once-exclusive item becomes thousands of roosters disseminated throughout the public domain.

As the project continued to evolve, questions arose around notions of origin, authenticity, and ownership of the rooster “image.” Templeman’s roosters are printed at about one eighth the scale of the original and the level of detail he achieves is astounding. The original artifact underwent multiple repairs, all of which are captured in the scan – and are represented in the Greenway roosters. Subtleties like these cracks and rivets help tell the story of the original rooster and become part of the story told in the “copies,” which blur the lines between authentic and manufactured.

Just a few decades ago, these artifacts couldn’t be replicated as quickly or easily as they can today with the technology of 3D scanning and printing. That said, Templeman’s rooster prototype differs in many ways – size, color, material, texture, weight – so, is it technically a “copy” or “replica” if it is visually different from the original rooster figurine that was scanned? Questions also abound surrounding the ownership of both the original rooster from the 19th century and the 2,017 plus copies that will be printed on The Greenway. Where does the line between the authentic original and the fabricated replica fall?

So how has the community taken to the artwork, which has been installed for nearly two months now? To experience the answer yourself, I invite you to spend some time with it – and witness passerby. It becomes immediately clear that they love it. Young and old, visiting from next door or across the world, local, exclaim as they see the rooster become clear. People stay for hours to watch the process and claim their own. It’s become a staple for local commuters, and a destination for those who have read about it in the news.

While the artwork has certainly won public favor, it hasn’t been a bump-free ride for the 3D printing machine itself. Even with all of Templeman’s trouble-shooting and preparing for every possible malfunctions, no new technology will be free of errors, especially one that runs 24 hours a day, 7 days a week – outside. To date there have been a number of failures, mutants, variations – whatever you might call them. To remedy the short-term bugs, Templeman has returned to the kiosk for occasional maintenance, and this he says, is one of the best parts for him: “Interaction with the public is an unintended consequence of the failures, but is turning out to be one of the most rewarding parts of the project.” During the design process, he was factoring in ways the public might vandalize the structure, but he’s found that just the opposite is happening – people are reaching out to him via twitter and Instagram to alert him if one something seems to be malfunctioning. “The true narrative here is that the public does not want to destroy but wants to be part of creating something,” said Templeman.

After a successful winter season where over 200 roosters were produced and given away, Make and Take leads us into the spring with a promise for innovation and an inquiring eye on the future of 3D printing technology. The project represents potential and possibilities while retaining strong roots and a sense of heritage. Templeman and NAPA’s collaboration exemplifies a successful interdisciplinary model that functions under the mission to introduce democratic, interactive artworks into our communities. As we look towards 2017 with many questions and uncertainties about what lies ahead, one thing is certain – this year Bostonians will experience 3D technology in a new way – and maybe even make a New Year resolution to claim one of the roosters as their own.